Our thanks to author R. Scott Anderson for this guest contribution.

Our thanks to author R. Scott Anderson for this guest contribution.

E=mc2. Everyone knows it. Everyone accepts it as valid. It’s Einstein’s unification of the Laws of Conservation of Mass and Energy, and as it is true in physics and it is true in every aspect of the physical universe, so it remains equally true in publishing.

Think of recent developments in publishing like putting on a pair of Spanx. A few years ago there were more than a dozen independent large publishing houses in the United States, now there are five. Just like putting on those stretchy underwear, you can mash stuff up as much as you want, but it’s got to go somewhere. And with the consolidation of so many publishing houses into megahouses, it was inevitable that there was going to be some redistribution within the ranks of book creation.

The major publishers have always been a conduit, seeking to guide all output into an orderly flow which they could control and exploit. It worked well and men like Maxwell Perkins, Robert Loomis, and Dan Menaker did their best to see wonderful books born into the literary stratosphere. And everything worked pretty well because offset printing was expensive, unwieldy, and the only way to get a book to market.

But with the arrival of a new and disruptive technology, digital printing, two things happened. An infinite number of new pathways to production opened, and because more individuals saw that they could access these pathways, the amount of product coming into the market expanded. As digital publishing and content production became readily available to the individual, the consolidation of major presses at one end created an anarchy of self-publishing on the other, to the point that people became willing to give their books away just to be read, because they could do it so inexpensively.

How can anything thrive in such a situation?

By evolutionary growth and change, the expansion of the interstices between mass and energy…to create a new opportunity.

I think small presses represent that area between the unified mass of the “Big Six, Five, Four, Three, Two, One…Amazon” unity, and the random diffusion and Brownian motion of self-publishing.

Algonquin Press was a trailblazer, a small North Carolina Press that sold itself to Workman Press based on the strength of its catalog, and now is a major part of the big picture in publishing. That was a path that many of us envied and sought to recreate, but there were other paths as well.

One of my absolute favorites was McSweeny’s, a San Francisco Press that seemed to be having the most fun in the business. Their product was unique, refreshing, and always unexpected in form and content, how can you not love that? Tin House, out of Portland, Oregon, started out as a literary magazine. They’re sixteen years old now, with a book-press that grows stronger with each passing year.

And I could go on and on and on… from Coffee House Press and Greywolf Press out of Minneapolis, to Melville House out of Brooklyn and Permanent Press out of Sag Harbour. From the big players like The New Press with fifty books a year and New York Review of Books Press, to new small presses like ours, China Grove Press, with our four to eight books a year, it sure seems like a resurgence.

And again, the question is why? I think it comes down to identity, a tone, a quality, a timber of editing and values. Each press is a singular thing, a craft beer in a world of Budweiser or home brews. A taste perhaps acquired, but once acquired something to be cherished and enjoyed.

I usually make someone angry by this point, and I don’t intend to, but I don’t mind either. I understand that there are many, many high quality self-published books and authors out there, well written, well edited, with wonderful graphic design and control, just as good as anything anywhere, but for every one of those there are thousands of far less consistently produced products. I’m first and always a writer, and I can tell you that even when I think I’ve done everything right, I usually haven’t, that’s where editing, continuity checks, and graphic layout assistance are most useful.

I usually make someone angry by this point, and I don’t intend to, but I don’t mind either. I understand that there are many, many high quality self-published books and authors out there, well written, well edited, with wonderful graphic design and control, just as good as anything anywhere, but for every one of those there are thousands of far less consistently produced products. I’m first and always a writer, and I can tell you that even when I think I’ve done everything right, I usually haven’t, that’s where editing, continuity checks, and graphic layout assistance are most useful.

I’m not saying that we get everything perfect or even uniform, but what you see in our work with young writers is a dedication to finding the beauty that is the essential core of the work. Working to make it look right on the page and giving the reader something that they can hold in their hand and see is a treasure.

At a conference recently I was on a panel and several of us who were small press publishers were putting our thoughts out and the consensus was that the reason everyone loved doing this was the joy that came from working with the authors. Then, unexpectedly, for some reason, without consideration, the truth for me just blurted out, “the authors are okay, but my love affair is with the words.”

Everyone in the audience frowned. But it’s true, it’s not the authors that I love, I don’t really care about them except as a source for the words. No matter how wonderful you are, if you can’t make your words move me, or excite me, or inflame me, or scare me, or write something that grabs me emotionally and viscerally to command my attention, there’s nothing I can do for you.

I love the words. I work with their placement on the page, I change spacing in a sentence, I edge something, or cut a word or alter a sequence to enhance the impact of what the author is trying to say, to get the best possible look of words on page, that’s what I love. I work with the authors to make the change, but I love the words.

I don’t love ebooks so much, kind of funny from a guy who used to own IsoLibris, an ebook company, but I don’t. They are crude, and have not been done well historically. Those things are changing, but with flowable text, the art is difficult. We are just starting to move to ebooks again, so I do have hope.

The big presses get it, they really do.

They understand the value of the small presses and respect what it is that they are doing. So much so, that there has been a spate of boutique presses coming out of the major publishers themselves. Amy Einhorn had great success with her eponymous press putting out books like The Help, and the Secret of Magic. Amy has moved on but she showed the value of what a concerted vision can accomplish. I’ve talked to Lee Boudreaux who recently left Little, Brown to start Lee Boudreaux Books with Hachette and know that she sees the same thing. Even famed author Pat Conroy has enjoyed success with his Story River Books imprint at USC Press.

So is this the “Golden Age” of the small press? Certainly from a monetary standpoint the future looks sustainable, otherwise why would the major presses bother at all? But more importantly, small presses are doing things that excite me, and that’s why I do this in the first place.

It’s frustrating, it steals time from my own writing, and it seems like the overarching goal for the immediate future is always survival. There is the constant battle in finding a distribution and a production cycle that allows books to be sold at the same discounts to booksellers the largest houses can give, but I keep doing it because after I’ve beaten my head against a thousand walls, fought to bring a spark in the writing into an ember, and see it flare reaching its own flame, I get to hold it up against the dark, offer it to the world, and say…hey, read this!

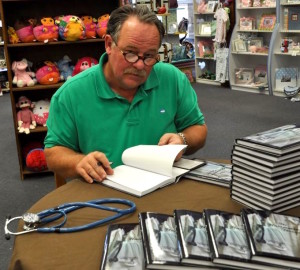

Russell Scott Anderson, M.D., is a radiation oncologist who serves as the medical director of Anderson Cancer Center in Meridian, Miss. He is a former Navy diver who worked in operations in the Middle East, Central America, and in support of the Navy’s EOD community, SEALS, the U.S. Army’s Green Berets, the Secret Service, and the New York Police Department at various times during his time in the service.

Russell Scott Anderson, M.D., is a radiation oncologist who serves as the medical director of Anderson Cancer Center in Meridian, Miss. He is a former Navy diver who worked in operations in the Middle East, Central America, and in support of the Navy’s EOD community, SEALS, the U.S. Army’s Green Berets, the Secret Service, and the New York Police Department at various times during his time in the service.

The father of seven has written the family oriented literary columns Una Voce and The Uncommon Thread in the Journal of the Mississippi State Medical Association. He has also served the Journal as the chairman of the editorial advisory board. A collection of his columns was published as The Uncommon Thread in 2012. He has also written as screenwriter R.S. Anderson on several feature films, he is the author of the novels Timedonors Wanted and The Hard Times under the pseudonym Russell Scott, and is the editor of the literary journal China Grove.

The father of seven has written the family oriented literary columns Una Voce and The Uncommon Thread in the Journal of the Mississippi State Medical Association. He has also served the Journal as the chairman of the editorial advisory board. A collection of his columns was published as The Uncommon Thread in 2012. He has also written as screenwriter R.S. Anderson on several feature films, he is the author of the novels Timedonors Wanted and The Hard Times under the pseudonym Russell Scott, and is the editor of the literary journal China Grove.

Small presses are easily putting out some of the most important work these days! Big kudos to Scott Anderson for his amazing books and small press and to Pat Conroy for starting his. And, congrats to Bren McClain…I’m one of the lucky ones who has already read One Good Mama Bone…and it’s a book that leaves you different (in a good way) after you’ve finished it! Shari, thanks for this and all the good information you constantly share!

Thanks, Julie! Agree on all counts – Bren’s book will be aces, and love that small presses are filling the gatekeeper void left by too much consolidation in the “big dog” space… putting out great literature, which is all us readers want!

Thanks, Shari. Critical role, indeed. Am loving what is coming out from small presses.

Interesting piece. I raise my cup of coffee to small presses and their critical role in publishing today. (I’m one of the fortunate ones — my novel, One Good Mama Bone, is coming out from Pat Conroy’s Story River Books in early 2017.)

Critical role indeed – With the dedicated folks in each of the small presses we know, seems will continue to play a significant role in publishing, especially as “gatekeepers” for quality literature! Can’t wait to read One Good Mama Bone – think it’s exactly representative of the sort of great reading we want to see from our small presses!